The Vampire was old, and no longer beautiful. In common with all

living things, she had aged, though very slowly, like the tall trees in

the park. Slender and gaunt and leafless, they stood out there, beyond

the long windows, rain-dashed in the grey morning. While she sat in her

high-backed chair in that corner of the room where the curtains of thick

yellow lace and the wine-coloured blinds kept every drop of daylight

out. In the glimmer of the ornate oil lamp, she had been reading. The

lamp came from a Russian palace. The book had once graced the library of

a corrupt pope named, in his temporal existence, Roderigo Borgia. Now

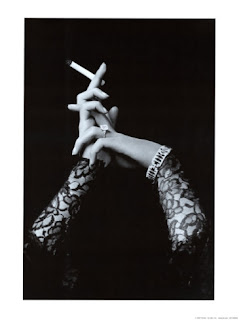

the Vampire's dry hands had fallen upon the page. She sat in her black

lace dress that was one hundred and eighty years of age, far younger

than she herself, and looked at the old man, streaked by the shine of

distant windows.

"You say you are tired, Vassu. I know how it is. To be so tired, and unable to rest. It is a terrible thing."

"But, Princess," said the old man quietly, "it is more than this. I am dying."

The Vampire stirred a little. The pale leaves of her hands rustled on the page. She stared, with an almost childlike wonder.

"Dying? Can this be? You are sure?"

The old man, very clean and neat in his dark clothing, nodded humbly.

"Yes, Princess."

"Oh, Vassu," she said, "are you glad?"

He seemed a little embarrassed. Finally he said:

"Forgive me, Princess, but I am very glad. Yes, very glad."

"I understand."

"Only," he said, "I am troubled for your sake."

"No, no," said the Vampire, with the fragile perfect courtesy of her

class and kind. "No, it must not concern you. You have been a good

servant. Far better than I might ever have hoped for. I am thankful,

Vassu, for all your care of me. I shall miss you. But you have earned…"

she hesitated. She said, "You have more than earned your peace."

"But you," he said.

"I shall do very well. My requirements are small, now. The days when I

was a huntress are gone, and the nights. Do you remember, Vassu?"

"I remember, Princess."

"When I was so hungry, and so relentless. And so lovely. My white

face in a thousand ballroom mirrors. My silk slippers stained with dew.

And my lovers waking in the cold morning, where I had left them. But

now, I do not sleep, I am seldom hungry. I never lust. I never love.

These are the comforts of old age. There is only one comfort that is

denied to me. And who knows. One day, I too…" She smiled at him. Her

teeth were beautiful, but almost even now, the exquisite points of the

canines quite worn away. "Leave me when you must," she said. "I shall

mourn you. I shall envy you. But I ask nothing more, my good and noble

friend."

The old man bowed his head.

"I have," he said, "a few days, a handful of nights. There is

something I wish to try to do in this time. I will try to find one who

may take my place."

The Vampire stared at him again, now astonished. "But Vassu, my irreplaceable help-it is no longer possible."

"Yes. If I am swift."

"The world is not as it was," she said, with a grave and dreadful wisdom.

He lifted his head. More gravely, he answered:

"The world is as it has always been, Princess. Only our perceptions of it have grown more acute. Our knowledge less bearable."

She nodded.

"Yes, this must be so. How could the world have changed so terribly? It must be we who have changed."

He trimmed the lamp before he left her.

Outside, the rain dripped steadily from the trees.

The city, in the rain, was not unlike a forest. But the old man, who

had been in many forests and many cities, had no special feeling for it.

His feelings, his senses, were primed to other things.

Nevertheless, he was conscious of his bizarre and anachronistic

effect, like that of a figure in some surrealist painting, walking the

streets in clothes of a bygone era, aware he did not blend with his

surroundings, nor render them homage of any kind. Yet even when, as

sometimes happened, a gang of children or youths jeered and called after

him the foul names he was familiar with in twenty languages, he neither

cringed nor cared. He had no concern for such things. He had been so

many places, seen so many sights; cities which burned or fell in ruin,

the young who grew old, as he had, and who died, as now, at last, he too

would die. This thought of death soothed him, comforted him, and

brought with it a great sadness, a strange jealousy. He did not want to

leave her. Of course he did not. The idea of her vulnerability in this

harsh world, not new in its cruelty but ancient, though freshly

recognised-it horrified him. This was the sadness. And the jealousy…

that, because he must try to find another to take his place. And that

other would come to be for her, as he had been.

The memories rose and sank in his brain like waking dreams all the

time he moved about the streets. As he climbed the steps of museums and

underpasses, he remembered other steps in other lands, of marble and

fine stone. And looking out from high balconies, the city reduced to a

map, he recollected the towers of cathedrals, the star-swept points of

mountains. And then at last, as if turning over the pages of a book

backwards, he reached the beginning.

There she stood, between two tall white graves, the chateau grounds

behind her, everything silvered in the dusk before the dawn. She wore a

ball dress, and a long white cloak. And even then, her hair was dressed

in the fashion of a century ago; dark hair, like black flowers.

He had known for a year before that he would serve her. The moment he

had heard them talk of her in the town. They were not afraid of her,

but in awe. She did not prey upon her own people, as some of her line

had done.

When he could get up, he went to her. He had kneeled, and stammered

something; he was only sixteen, and she not much older. But she had

simply looked at him quietly and said: "I know. You are welcome." The

words had been in a language they seldom spoke together now. Yet always,

when he recalled that meeting, she said them in that tongue, and with

the same gentle inflexion.

All about, in the small caf

He rose, and left the caf

A step brushed the pavement, perhaps twenty feet behind him. The old

man did not hesitate. He stepped on, and into an alleyway that ran

between the high buildings. The steps followed him; he could not hear

them all, only one in seven, or eight. A little wire of tension began to

draw taut within him, but he gave no sign. Water trickled along the

brickwork beside him, and the noise of the city was lost.

Abruptly, a hand was on the back of his neck, a capable hand, warm and sure, not harming him yet, almost the touch of a lover.

"That's right, old man. Keep still. I'm not going to hurt you, not if you do what I say."

He stood, the warm and vital hand on his neck, and waited.

"All right," said the voice, which was masculine and young and with

some other elusive quality to it. "Now let me have your wallet."

The old man spoke in a faltering tone, very foreign, very fearful. "I have-no wallet."

The hand changed its nature, gripped him, bit.

"Don't lie. I can hurt you. I don't want to, but I can. Give me whatever money you have."

"Yes," he faltered, "yes-yes-"

And slipped from the sure and merciless grip like water, spinning,

gripping in turn, flinging away-there was a whirl of movement.

The old man's attacker slammed against the wet grey wall and rolled

down it. He lay on the rainy debris of the alley floor, and stared up,

too surprised to look surprised.

This had happened many times before. Several had supposed the old man

an easy mark, but he had all the steely power of what he was. Even now,

even dying, he was terrible in his strength. And yet, though it had

happened often, now it was different. The tension had not gone away.

Swiftly, deliberately, the old man studied the young one.

Something struck home instantly. Even sprawled, the adversary was

peculiarly graceful, the grace of enormous physical coordination. The

touch of the hand, also, impervious and certain-there was strength here,

too. And now the eyes. Yes, the eyes were steady, intelligent, and with

a curious lambency, an innocence-

"Get up," the old man said. He had waited upon an aristocrat. He had

become one himself, and sounded it. "Up. I will not hit you again."

The young man grinned, aware of the irony. The humour flitted through

his eyes. In the dull light of the alley, they were the colour of

leopards-not the eyes of leopards, but their

pelts.

"Yes, and you could, couldn't you, granddad."

"My name," said the old man, "is Vasyelu Gorin. I am the father to

none, and my nonexistent sons and daughters have no children. And you?"

"My name," said the young man, "is Snake."

The old man nodded. He did not really care about names, either.

"Get up, Snake. You attempted to rob me, because you are poor, having no work and no wish for work. I will buy you food, now."

The young man continued to lie, as if at ease, on the ground.

"Why?"

"Because I want something from you."

"What? You're right. I'll do almost anything, if you pay me enough. So you can tell me."

The old man looked at the young man called Snake, and knew that all

he said was a fact. Knew that here was one who had stolen and whored,

and stolen again when the slack bodies slept, both male and female,

exhausted by the sexual vampirism he had practised on them, drawing

their misguided souls out through their pores as later he would draw the

notes from purse and pocket. Yes, a vampire. Maybe a murderer, too.

Very probably a murderer.

"If you will do anything," said the old man, "I need not tell you beforehand. You will do it anyway."

"Almost anything, is what I said."

"Advise me then," said Vasyelu Gorin, the servant of the Vampire,

"what you will not do. I shall then refrain from asking it of you."

The young man laughed. In one fluid movement he came to his feet. When the old man walked on, he followed.

Testing him, the old man took Snake to an expensive restaurant, far

up on the white hills of the city, where the glass geography nearly

scratched the sky. Ignoring the mud on his dilapidated leather jacket,

Snake became a flawless image of decorum, became what is always

ultimately respected, one who does not care. The old man, who also did

not care, appreciated this act, but knew it was nothing more. Snake had

learned how to be a prince. But he was a gigolo with a closet full of

skins to put on. Now and then the speckled leopard eyes, searching,

wary, would give him away.

After the good food and the excellent wine, the cognac, the

cigarettes taken from the silver box-Snake had stolen three, but,

stylishly overt, had left them sticking like porcupine quills from his

breast pocket-they went out again into the rain.

The dark was gathering, and Snake solicitously took the old man's

arm. Vasyelu Gorin dislodged him, offended by the cheapness of the

gesture after the acceptable one with the cigarettes.

"Don't you like me any more?" said Snake. "I can go now, if you want. But you might pay for my wasted time."

"Stop that," said Vasyelu Gorin. "Come along."

Smiling, Snake came with him. They walked, between the glowing

pyramids of stores, through shadowy tunnels, over the wet paving. When

the thoroughfares folded away and the meadows of the great gardens

began, Snake grew tense. The landscape was less familiar to him,

obviously. This part of the forest was unknown.

Trees hung down from the air to the sides of the road.

"I could kill you here," said Snake. "Take your money, and run."

"You could try," said the old man, but he was becoming weary. He was

no longer certain, and yet, he was sufficiently certain that his

jealousy had assumed a tinge of hatred. If the young man were stupid

enough to set on him, how simple it would be to break the columnar neck,

like pale amber, between his fleshless hands. But then, she would know.

She would know he had found for her, and destroyed the finding. And she

would be generous, and he would leave her, aware he had failed her,

too.

When the huge gates appeared, Snake made no comment. He seemed, by

then, to anticipate them. The old man went into the park, moving quickly

now, in order to outdistance his own feelings. Snake loped at his side.

Three windows were alight, high in the house. Her windows. And as

they came to the stair that led up, under its skeins of ivy, into the

porch, her pencil-thin shadow passed over the lights above, like smoke,

or a ghost.

"I thought you lived alone," said Snake. "I thought you were lonely."

The old man did not answer any more. He went up the stair and opened

the door. Snake came in behind him, and stood quite still, until Vasyelu

Gorin had found the lamp in the niche by the door, and lit it.

Unnatural stained glass flared in the door panels, and the window-niches

either side, owls and lotuses and far-off temples, scrolled and

luminous, oddly aloof.

Vasyelu began to walk toward the inner stair.

"Just a minute," said Snake. Vasyelu halted, saying nothing. "I'd

just like to know," said Snake, "how many of your friends are here, and

just what your friends are figuring to do, and how I fit into their

plans."

The old man sighed.

"There is one woman in the room above. I am taking you to see her.

She is a Princess. Her name is Darejan Draculas." He began to ascend the

stair.

Left in the dark, the visitor said softly:

"What?"

"You think you have heard the name. You are correct. But it is another branch."

He heard only the first step as it touched the carpeted stair. With a

bound, the creature was upon him, the lamp was lifted from his hand.

Snake danced behind it, glittering and unreal.

"Dracula," he said.

"Draculas. Another branch."

"A vampire."

"Do you believe in such things?" said the old man. "You should, living as you do, preying as you do."

"I never," said Snake, "pray."

"Prey," said the old man. "Prey upon. You cannot even speak your own

language. Give me the lamp, or shall I take it? The stair is steep. You

may be damaged, this time. Which will not be good for any of your

trades."

Snake made a little bow, and returned the lamp.

They continued up the carpeted hill of stair, and reached a landing and so a passage, and so her door.

The appurtenances of the house, even glimpsed in the erratic fleeting

of the lamp, were very gracious. The old man was used to them, but

Snake, perhaps, took note. Then again, like the size and importance of

the park gates, the young thief might well have anticipated such

elegance.

And there was no neglect, no dust, no air of decay, or, more tritely,

of the grave. Women arrived regularly from the city to clean, under

Vasyelu Gorin's stern command; flowers were even arranged in the salon

for those occasions when the Princess came downstairs. Which was rarely,

now. How tired she had grown. Not aged, but bored by life. The old man

sighed again, and knocked upon her door.

Her response was given softly. Vasyelu Gorin saw, from the tail of

his eye, the young man's reaction, his ears almost pricked, like a

cat's.

"Wait here," Vasyelu said, and went into the room, shutting the door, leaving the other outside it in the dark.

The windows which had shone bright outside were black within. The candles burned, red and white as carnations.

The Vampire was seated before her little harpsichord. She had

probably been playing it, its song so quiet it was seldom audible beyond

her door. Long ago, nonetheless, he would have heard it. Long ago-

"Princess," he said, "I have brought someone with me."

He had not been sure what she would do, or say, confronted by the

actuality. She might even remonstrate, grow angry, though he had not

often seen her angry. But he saw now she had guessed, in some tangible

way, that he would not return alone, and she had been preparing herself.

As she rose to her feet, he beheld the red satin dress, the jewelled

silver crucifix at her throat, the trickle of silver from her ears. On

the thin hands, the great rings throbbed their sable colours. Her hair,

which had never lost its blackness, abbreviated at her shoulders and

waved in a fashion of only twenty years before, framed the starved bones

of her face with a savage luxuriance. She was magnificent. Gaunt,

elderly, her beauty lost, her heart dulled, yet-magnificent, wondrous.

He stared at her humbly, ready to weep because, for the half of one half-moment, he had doubted.

"Yes," she said. She gave him the briefest smile, like a swift caress. "Then I will see him, Vassu."

Snake was seated cross-legged a short distance along the passage. He had discovered, in the dark, a slender Chinese vase of the

yang ts'ai palette, and held it between his hands, his chin resting on the brim.

"Shall I break this?" he asked.

Vasyelu ignored the remark. He indicated the opened door.

"You may go in now."

"May I? How excited you're making me."

Snake flowed upright. Still holding the vase, he went through into

the Vampire's apartment. The old man came into the room after him,

placing his black-garbed body, like a shadow, by the door, which he left

now standing wide. The old man watched Snake.

Circling slightly, perhaps unconsciously, he had approached a third

of the chamber's length towards the woman. Seeing him from the back,

Vasyelu Gorin was able to observe all the play of tautening muscles

along the spine, like those of something readying itself to spring, or

to escape. Yet, not seeing the face, the eyes, was unsatisfactory. The

old man shifted his position, edged shadow-like along the room's

perimeter, until he had gained a better vantage.

"Good evening," the Vampire said to Snake. "Would you care to put

down the vase? Or, if you prefer, smash it. Indecision can be

distressing."

"Perhaps I'd prefer to keep the vase."

"Oh, then do so, by all means. But I suggest you allow Vasyelu to

wrap it up for you, before you go. Or someone may rob you on the

street."

Snake pivotted, lightly, like a dancer, and put the vase on a side-table. Turning again, he smiled at her.

"There are so many valuable things here. What shall I take? What about the silver cross you're wearing?"

The Vampire also smiled.

"An heirloom. I am rather fond of it. I do not recommend you should try to take that."

Snake's eyes enlarged. He was naive, amazed.

"But I thought, if I did what you wanted, if I made you happy-I could have whatever I liked. Wasn't that the bargain?"

"And how would you propose to make me happy?"

Snake went close to her; he prowled about her, very slowly.

Disgusted, fascinated, the old man watched him. Snake stood behind her,

leaning against her, his breath stirring the filaments of her hair. He

slipped his left hand along her shoulder, sliding from the red satin to

the dry uncoloured skin of her throat. Vasyelu remembered the touch of

the hand, electric, and so sensitive, the fingers of an artist or a

surgeon.

The Vampire never changed. She said:

"No. You will not make me happy, my child."

"Oh," Snake said into her ear. "You can't be certain. If you like, if you really like, I'll let you drink my blood."

The Vampire laughed. It was frightening. Something dormant yet

intensely powerful seemed to come alive in her as she did so, like flame

from a finished coal. The sound, the appalling life, shook the young

man away from her. And for an instant, the old man saw fear in the

leopard-yellow eyes, a fear as intrinsic to the being of Snake as to

cause fear was intrinsic to the being of the Vampire.

And, still blazing with her power, she turned on him.

"What do you think I am?" she said, "some senile hag greedy to rub

her scaly flesh against your smoothness; some hag you can, being

yourself without sanity or fastidiousness, corrupt with the phantoms,

the left-overs of pleasure, and then murder, tearing the gems from her

fingers with your teeth? Or I am a perverted hag, wanting to lick up

your youth with your juices. Am I that? Come now," she said, her fire

lowering itself, crackling with its amusement, with everything she held

in check, her voice a long, long pin, skewering what she spoke to

against the farther wall. "Come now. How can I be such a fiend, and wear

the crucifix on my breast? My ancient, withered, fallen, empty breast.

Come now. What's in a name?"

As the pin of her voice came out of him, the young man pushed himself

away from the wall. For an instant there was an air of panic about him.

He was accustomed to the characteristics of the world. Old men creeping

through rainy alleys could not strike mighty blows with their iron

hands. Women were moths that burnt, but did not burn, tones of tinsel

and pleading, not razor blades.

Snake shuddered all over. And then his panic went away.

Instinctively, he told something from the aura of the room itself.

Living as he did, generally he had come to trust his instincts.

He slunk back to the woman, not close, this time, no nearer than two yards.

"Your man over there," he said, "he took me to a fancy restaurant. He

got me drunk. I say things when I'm drunk I shouldn't say. You see? I'm

a lout. I shouldn't be here in your nice house. I don't know how to

talk to people like you. To a lady. You see? But I haven't any money.

None. Ask him. I explained it all. I'll do anything for money. And the

way I talk. Some of them like it. You see? It makes me sound dangerous.

They like that. But it's just an act." Fawning on her, bending on her

the groundless glory of his eyes, he had also retreated, was almost at

the door.

The Vampire made no move. Like a marvelous waxwork she dominated the

room, red and white and black, and the old man was only a shadow in a

corner.

Snake darted about and bolted. In the blind lightlessness, he skimmed

the passage, leapt out in space upon the stairs, touched, leapt,

touched, reached the open area beyond. Some glint of star-shine revealed

the stained glass panes in the door. As it crashed open, he knew quite

well that he had been let go. Then it slammed behind him and he pelted

through ivy and down the outer steps, and across the hollow plain of

tall wet trees.

So much, infallibly, his instincts had told him. Strangely, even as

he came out of the gates upon the vacant road, and raced towards the

heart of the city, they did not tell him he was free.

"Do you recollect," said the Vampire, "you asked me, at the very beginning, about the crucifix."

"I do recollect, Princess. It seemed odd to me, then. I did not understand, of course."

"And you," she said. "How would you have it, after-" She waited. She said, "After you leave me."

He rejoiced that his death would cause her a momentary pain. He could

not help that, now. He had seen the fire wake in her, flash and scald

in her, as it had not done for half a century, ignited by the presence

of the thief, the gigolo, the parasite.

"He," said the old man, "is young and strong, and can dig some pit for me."

"And no ceremony?" She had overlooked his petulance, of course, and her tact made him ashamed.

"Just to lie quiet will be enough," he said, "but thank you,

Princess, for your care. I do not suppose it will matter. Either there

is nothing, or there is something so different I shall be astonished by

it."

"Ah, my friend. Then you do not imagine yourself damned?"

"No," he said. "No, no." And all at once there was passion in his

voice, one last fire of his own to offer her. "In the life you gave me, I

was blessed."

She closed her eyes, and Vasyelu Gorin perceived he had wounded her

with his love. And, no longer peevishly, but in the way of a lover, he

was glad.

Next day, a little before three in the afternoon, Snake returned.

A wind was blowing, and seemed to have blown him to the door in a

scurry of old brown leaves. His hair was also blown, and bright, his

face wind-slapped to a ridiculous freshness. His eyes, however, were

heavy, encircled, dulled. The eyes showed, as did nothing else about

him, that he had spent the night, the forenoon, engaged in his second

line of commerce. They might have drawn thick curtains and blown out the

lights, but that would not have helped him. The senses of Snake were

doubly acute in the dark, and he could see in the dark, like a lynx.

"Yes?" said the old man, looking at him blankly, as if at a tradesman.

"Yes," said Snake, and came by him into the house.

Vasyelu did not stop him. Of course not. He allowed the young man, and all his blown gleamingness and his wretched rou

The blinds, a sombre ivory colour, were down, and the lamps had been

lit; on a polished table hothouse flowers foamed from a jade bowl. A

second door stood open on the small library, the soft glow of the lamps

trembling over gold-worked spines, up and up, a torrent of static,

priceless books.

Snake went into and around the library, and came out.

"I didn't take anything."

"Can you even read?" snapped Vasyelu Gorin, remembering when he could

not, a wood-cutter's fifth son, an oaf and a sot, drinking his way or

sleeping his way through a life without windows or vistas, a mere

blackness of error and unrecognised boredom. Long ago. In that little

town cobbled together under the forest. And the chateau with its starry

lights, the carriages on the road, shining, the dark trees either side.

And bowing in answer to a question, lifting a silver comfit box from a

pocket as easily as he had lifted a coin the day before…

Snake sat down, leaning back relaxedly in the chair. He was not

relaxed, the old man knew. What was he telling himself? That there was

money here, eccentricity to be battened upon. That he could take her,

the old woman, one way or another. There were always excuses that one

could make to oneself.

When the Vampire entered the room, Snake, practised, a gigolo, came

to his feet. And the Vampire was amused by him, gently now. She wore a

bone-white frock that had been sent from Paris last year. She had never

worn it before. Pinned at the neck was a black velvet rose with a single

drop of dew shivering on a single petal: a pearl that had come from the

crown jewels of a czar. Her tact, her peerless tact.

Naturally, the pearl was saying, this is why you have come back. Naturally. There is nothing to fear.

Vasyelu Gorin left them. He returned later with the decanters and

glasses. The cold supper had been laid out by people from the city who

handled such things, pthen against the house, and, roused by the

brilliantly lighted rooms, a moth was dashing itself between the candles

and the coloured fruits. The old man caught it in a crystal goblet,

took it away, let it go into the darkness. For a hundred years and more,

he had never killed anything.

Sometimes, he heard them laugh. The young man's laughter was at first

too eloquent, too beautiful, too unreal. But then, it became ragged,

boisterous; it became genuine.

The wind blew stonily. Vasyelu Gorin imagined the frail moth beating

its wings against the huge wings of the wind, falling spent to the

ground. It would be good to rest.

In the last half hour before dawn, she came quietly from the salon,

and up the stair. The old man knew she had seen him as he waited in the

shadows. That she did not look at him or call to him was her attempt to

spare him this sudden sheen that was upon her, its direct and pitiless

glare. So he glimpsed it obliquely, no more. Her straight pale figure

ascending, slim and limpid as a girl's. Her eyes were young, full of a

primal refinding, full of utter newness.

In the salon, Snake slept under his jacket on the long white couch,

its brocaded cushions beneath his cheek. Would he, on waking, carefully

examine his throat in a mirror?

The old man watched the young man sleeping. She had taught Vasyelu

Gorin how to speak five languages, and how to read three others. She had

allowed him to discover music, and art, history and the stars;

profundity, mercy. He had found the closed tomb of life opened out on

every side into unbelievable, inexpressible landscapes. And yet, and

yet. The journey must have its end. Worn out with ecstasy and

experience, too tired any more to laugh with joy. To rest was

everything. To be still. Only she could continue, for only she could be

eternally reborn. For Vasyelu, once had been enough.

He left the young man sleeping. Five hours later, Snake was noiselessly gone. He had taken all the cigarettes, but nothing else.

Snake sold the cigarettes quickly. At one of the cafcity.

Some of the day, he walked.

A hunter, he distrusted the open veldt of daylight. There was too

little cover, and equally too great cover for the things he stalked. In

the afternoon, he sat in the gardens of a museum. Students came and

went, seriously alone, or in groups riotously. Snake observed them. They

were scarcely younger than he himself, yet to him, another species. Now

and then a girl, catching his eye, might smile, or make an attempt to

linger, to interest him. Snake did not respond. With the economic

contempt of what he had become, he dismissed all such sexual encounters.

Their allure, their youth, these were commodities valueless in others.

They would not pay him.

The old woman, however, he did not dismiss. How old was she? Sixty,

perhaps-no, much older. Ninety was more likely. And yet, her face, her

neck, her hands were curiously smooth, unlined. At times, she might only

have been fifty. And the dyed hair, which should have made her seem

raddled, somehow enhanced the illusion of a young woman.

Yes, she fascinated him. Probably she had been an actress. Foreign,

theatrical-rich. If she was prepared to keep him, thinking him

mistakenly her pet cat, then he was willing, for a while. He could steal

from her when she began to cloy and he decided to leave.

Yet, something in the uncomplexity of these thoughts disturbed him.

The first time he had run away, he was unsure now from what. Not the

vampire name, certainly, a stage name-

Draculas-what else? But from something-some awareness of fate for

which idea his vocabulary had no word, and no explanation. Driven once

away, driven thereafter to return, since it was foolish not to. And she

had known how to treat him. Gracefully, graciously. She would be

honourable, for her kind always were. Used to spending money for what

they wanted, they did not baulk at buying people, too. They had never

forgotten flesh, also, had a price, since their roots were firmly locked

in an era when there had been slaves.

But. But he would not, he told himself, go there tonight. No. It

would be good she should not be able to rely on him. He might go

tomorrow, or the next day, but not tonight.

The turning world lifted away from the sun, through a winter sunset,

into darkness. Snake was glad to see the ending of the light, and false

light instead spring up from the apartment blocks, the caf

He moved out on to the wide pavement of a street, and a man came and

took his arm on the right side, another starting to walk by him on the

left.

"Yes, this is the one, the one calls himself Snake."

"Are you?" the man who walked beside him asked.

"Of course it is," said the first man, squeezing his arm. "Didn't we

have an exact description? Isn't he just the way he was described?"

"And the right place, too," agreed the other man, who did not hold him. "The right area."

The men wore neat nondescript clothing. Their faces were sallow and

smiling, and fixed. This was a routine with which both were familiar.

Snake did not know them, but he knew the touch, the accent, the smiling

fixture of their masks. He had tensed. Now he let the tension melt away,

so they should see and feel it had gone.

"What do you want?"

The man who held his arm only smiled.

The other man said, "Just to earn our living."

"Doing what?"

On either side the lighted street went by. Ahead, at the street's

corner, a vacant lot opened where a broken wall lunged away into the

shadows.

"It seems you upset someone," said the man who only walked. "Upset them badly."

"I upset a lot of people," Snake said.

"I'm sure you do. But some of them won't stand for it."

"Who was this? Perhaps I should see them."

"No. They don't want that. They don't want you to see anybody." The black turn was a few feet away.

"Perhaps I can put it right."

"No. That's what we've been paid to do."

"But if I don't know-" said Snake, and lurched against the man who

held his arm, ramming his fist into the soft belly. The man let go of

him and fell. Snake ran. He ran past the lot, into the brilliant glare

of another street beyond, and was almost laughing when the thrown knife

caught him in the back.

The lights turned over. Something hard and cold struck his chest, his

face. Snake realized it was the pavement. There was a dim blurred

noise, coming and going, perhaps a crowd gathering. Someone stood on his

ribs and pulled the knife out of him and the pain began.

"Is that it?" a choked voice asked some way above him: the man he had punched in the stomach.

"It'll do nicely."

A new voice shouted. A car swam to the kerb and pulled up raucously.

The car door slammed, and footsteps went over the cement. Behind him,

Snake heard the two men walking briskly away.

Snake began to get up, and was surprised to find he was unable to.

"What happened?" someone asked, high, high above.

"I don't know."

A woman said softly, "Look, there's blood-"

Snake took no notice. After a moment he tried again to get up, and

succeeded in getting to his knees. He had been hurt, that was all. He

could feel the pain, no longer sharp, blurred, like the noise he could

hear, coming and going. He opened his eyes. The light had faded, then

came back in a long wave, then faded again. There seemed to be only five

or six people standing around him. As he rose, the nearer shapes backed

away.

"He shouldn't move," someone said urgently.

A hand touched his shoulder, fluttered off, like an insect.

The light faded into black, and the noise swept in like a tide,

filling his ears, dazing him. Something supported him, and he shook it

from him-a wall-

"Come back, son," a man called. The lights burned up again,

reminiscent of a cinema. He would be all right in a moment. He walked

away from the small crowd, not looking at them. Respectfully, in awe,

they let him go, and noted his blood trailing behind him along the

pavement.

The French clock chimed sweetly in the salon; it was seven. Beyond the window, the park was black. It had begun to rain again.

The old man had been watching from the downstairs window for rather

more than an hour. Sometimes, he would step restlessly away, circle the

room, straighten a picture, pick up a petal discarded by the dying

flowers. Then go back to the window, looking out at the trees, the rain

and the night.

Less than a minute after the chiming of the clock, a piece of the

static darkness came away and began to move, very slowly, towards the

house.

Vasyelu Gorin went out into the hall. As he did so, he glanced

towards the stairway. The lamp at the stairhead was alight, and she

stood there in its rays, her hands lying loosely at her sides, elegant

as if weightless, her head raised.

"Princess?"

"Yes, I know. Please hurry, Vassu. I think there is scarcely any margin left."

The old man opened the door quickly. He sprang down the steps as

lightly as a boy of eighteen. The black rain swept against his face,

redolent of a thousand memories, and he ran through an orchard in

Burgundy, across a hillside in Tuscany, along the path of a wild garden

near St. Petersburg that was St. Petersburg no more, until he reached

the body of a young man lying over the roots of a tree.

The old man bent down, and an eye opened palely in the dark and looked at him.

"Knifed me," said Snake. "Crawled all this way."

Vasyelu Gorin leaned in the rain to the grass of France, Italy and

Russia, and lifted Snake in his arms. The body lolled, heavy, not

helping him. But it did not matter. How strong he was, he might marvel

at it, as he stood, holding the young man across his breast, and

turning, ran back towards the house.

"I don't know," Snake muttered, "don't know who sent them. Plenty would like to-How bad is it? I didn't think it was so bad."

The ivy drifted across Snake's face and he closed his eyes.

As Vasyelu entered the hall, the Vampire was already on the lowest

stair. Vasyelu carried the dying man across to her, and laid him at her

feet. Then Vasyelu turned to leave.

"Wait," she said.

"No, Princess. This is a private thing. Between the two of you, as

once it was between us. I do not want to see it, Princess. I do not want

to see it with another."

She looked at him, for a moment like a child, sorry to have

distressed him, unwilling to give in. Then she nodded. "Go then, my

dear."

He went away at once. So he did not witness it as she left the stair,

and knelt beside Snake on the Turkish carpet newly coloured with blood.

Yet, it seemed to him he heard the rustle her dress made, like thin

crisp paper, and the whisper of the tiny dagger parting her flesh, and

then the long still sigh.

He walked down through the house, into the clean and frigid modern

kitchen full of electricity. There he sat, and remembered the forest

above the town, the torches as the yelling aristocrats hunted him for

his theft of the comfit box, the blows when they caught up with him. He

remembered, with a painless unoppressed refinding, what it was like to

begin to die in such a way, the confused anger, the coming and going of

tangible things, long pulses of being alternating with deep valleys of

non-being. And then the agonised impossible crawl, fingers in the earth

itself, pulling him forward, legs sometimes able to assist, sometimes

failing, passengers which must be dragged with the rest. In the

graveyard at the edge of the estate, he ceased to move. He could go no

farther. The soil was cold, and the white tombs, curious petrified

vegetation over his head, seemed to suck the black sky into themselves,

so they darkened, and the sky grew pale.

But as the sky was drained of its blood, the foretaste of day began to possess it. In less than an hour, the sun would rise.

He had heard her name, and known he would eventually come to serve

her. The way in which he had known, both for himself and for the young

man called Snake, had been in a presage of violent death.

All the while, searching through the city, there had been no one with

that stigma upon them, that mark. Until, in the alley, the warm hand

gripped his neck, until he looked into the leopard-coloured eyes. Then

Vasyelu saw the mark, smelled the scent of it like singed bone.

How Snake, crippled by a mortal wound, bleeding and semi-aware, had

brought himself such a distance, through the long streets hard as nails,

through the mossy garden-land of the rich, through the colossal gates,

over the watery, night-tuned plain, so far, dying, the old man did not

require to ask, or to be puzzled by. He, too, had done such a thing,

more than two centuries ago. And there she had found him, between the

tall white graves. When he could focus his vision again, he had looked

and seen her, the most beautiful thing he ever set eyes upon. She had

given him her blood. He had drunk the blood of Darejan Draculas, a

princess, a vampire. Unique elixir, it had saved him. All wounds had

healed. Death had dropped from him like a torn skin, and everything he

had been-scavenger, thief, brawler, drunkard, and, for a certain number

of coins,

whore-each of these things had crumbled away. Standing up, he had

trodden on them, left them behind. He had gone to her, and kneeled down

as, a short while before, she had kneeled by him, cradling him, giving

him the life of her silver veins.

And this, all this, was now for the other. Even her blood, it seemed,

did not bestow immortality, only longevity, at last coming to a stop

for Vasyelu Gorin. And so, many many decades from this night the other,

too, would come to the same hiatus. Snake, too, would remember the

waking moment, conscious another now endured the stupefied thrill of it,

and all that would begin thereafter.

Finally, with a sort of guiltiness, the old man left the hygienic

kitchen and went back towards the glow of the upper floor, stealing out

into the shadow at the light's edge.

He understood that she would sense him there, untroubled by his presence-had she not been prepared to let him remain?

It was done.

Her dress was spread like an open rose, the young man lying against

her, his eyes wide, gazing up at her. And she would be the most

beautiful thing that he had ever seen. All about, invisible, the shed

skins of his life, husks he would presently scuff uncaringly underfoot.

And she?

The Vampire's head inclined toward Snake. The dark hair fell softly.

Her face, powdered by the lampshine, was young, was full of vitality,

serene vivacity, loveliness. Everything had come back to her. She was

reborn.

Perhaps it was only an illusion.

The old man bowed his head, there in the shadows. The jealousy, the

regret were gone. In the end, his life with her had become only another

skin that he must cast. He would have the peace that she might never

have, and be glad of it. The young man would serve her, and she would be

huntress once more, and dancer, a bright phantom gliding over the

ballroom of the city, this city and others, and all the worlds of land

and soul between.

Vasyelu Gorin stirred on the platform of his existence. He would

depart now, or very soon; already he heard the murmur of the approaching

train. It would be simple, this time, not like the other time at all.

To go willingly, everything achieved, in order. Knowing she was safe.

There was even a faint colour in her cheeks, a blooming. Or maybe, that was just a trick of the lamp.

The old man waited until they had risen to their feet, and walked

together quietly into the salon, before he came from the shadows and

began to climb the stairs, hearing the silence, their silence, like that

of new lovers.

At the head of the stair, beyond the lamp, the dark was gentle, soft

as the Vampire's hair. Vasyelu walked forward into the dark without

misgiving, tenderly.

How he had loved her.